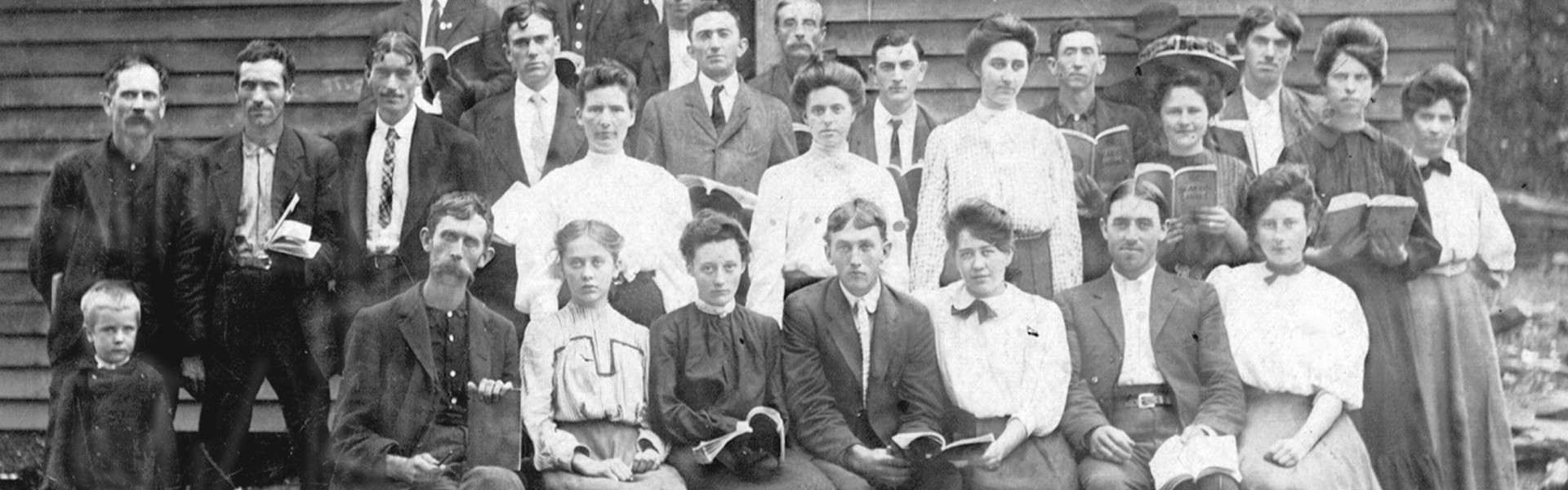

Shaped-note singing school, Altamont, NC circa 1910. Lenoir Franklin, left with oblong book and tuning fork, is singing master.

The Book Itself

The Editor's Preface To The 1979 Reprint

By Brent Howard Holcomb

Christian Harmony was published in its first edition in 1867. It retained a number of the songs from the various editions of Walker’s Southern Harmony (1835-1854), but moved in a more progressive vein including “a large number of new tunes from eminent composers never before published.” The physical appearance of the Christian Harmony and the music therein is quite different from hymnals of today, but typical of its era. The obvious difference in appearance is the “end-opener” or oblong format. As for the music, each song is written on four staves (or rarely five, with an added part), and Walker has consistently added an alto part to songs previously lacking it. (A few years earlier in editions of Southern Harmony, as with other tune books, an alto part was the exception rather than the rule). The bottom staff is bass; the next staff, tenor (sometimes called “soprano”) which is the melody line. The third staff was alto; and the top staff, treble (commonly called “high line”). Anyone attempting to play these on a keyboard instrument encounters the difficulty of reading four staves and reaching some impossible intervals. Obviously then, this music was not meant to be played, but sung a capella, i.e.; without accompaniment. Though occasionally a few songs are accompanied, this accompaniment tends to hamper the singing more than aid it. The different shapes of the notes are explained very well in “The Rudiments of Music” in this publication. In the preface Walker explains his change from the four note (or fa-so-la) system, wherein the scale was fa so la fa so la mi fa, to the seven-shape or do-re-mi system. This change was made in the 1866 [1867]edition of Christian Harmony. All editions of his earlier Southern Harmony had used the fa-so-la system. Walker apparently was allied with progress in this way as well, and forsook his old system. The more conservative Sacred Harp preserves the four-note system to this day.

The music itself derives from various sources. Walker included songs written much before his time that had maintained popularity: New England fuguing tunes such as Daniel Read’s “Sherburne” and Billings’ “Easter Anthem,” though erroneously ascribed to Stephenson. Some tunes which had not heretofore been written down, Walker notated and harmonized and wrote his name as composer. One of these was “French Broad,” which bears the notation “I learned the air of this tune of my dear mother, when only five years old.” Walker, of course, was composer of many songs himself. If we may rely on his memory, his “first original piece” was “Solemn Call,” written in 1827. The still popular “Heavenly Armor” was written the next year. “The Lone Pilgrim” ascribed to B. F. White in the Sacred Harp and to Walker here, is a Scottish folk song “Braes o’ Balquhidder” transformed, and “Thorny Desert” and “Something New” are perhaps folk-hymn variants of Scotch-Irish reels. Walker also included compositions by native South Carolinians and relatives such as William Bobo of Union County, S. C., David Walker, William Golightly, and Rev. John G. Landrum. Walker included a sampling of old Psalm tunes such as “Old Hundred” and “Ninety Fifth.” Obviously he admired the work of William Hauser from the number of songs borrowed from him. William Walker himself realized variants of the same tune, as by his notation on page 119, concerning “Weary Souls” and “Redeeming Love.” The song “The Saints Bound for Heaven” is ascribed here to William Walker and J. King. This must have been Joel King, older brother of E. J. King (though assigned to the latter in the Sacred Harp). This tune having been written in 1834, E. J. King could hardly have been the collaborator, being only about thirteen years old at the time.

With his idea of progress in changing from four to seven shapes, came also some change of music. Walker adopted a few of the more bland, urban Gospel songs such as “Pass Me Not” and “Night is Coming.” A crude version of “Ein Feste Burg” titled “Reformation” is even found here. The 1873 edition . . . is only slightly different from the first, or 1866 edition. Walker included several compositions not in the 1867 edition, such as “Soft Music,” “Hicks’ Farewell,” and “Passing Away.” Oddly enough, the popularity of some of Walker’s music lies mainly in the Sacred Harp: “Hallelujah” and “Heavenly Armor” remain popular at Sacred Harp singings today. Christian Harmony singings are still held today particularly in southern Alabama and western North Carolina, with many singers making long journeys to attend. Although some contemporary hymnals employ tunes from Walker’s publications, their original settings are so altered that the true flavor and vitality of the music is all but destroyed. The present edition will hopefully help to retain the original beauty of this music.

As for the man himself, William Walker was born in Union District, South Carolina, May 6, 1809, the son of Absalom and Susan (Jackson) Walker. His mother was the daughter of Frederick Sr. and Mary (Greer) Jackson. Therefore he was related to many early families of that area. Walker grew up in Lower Fairforest Baptist Church in Union District, and probably attended occasionally the nearby Padgett’s Creek Baptist Church, where his parents had been members earlier. In both of these congregations music was important, as is indicated by the frequent attention paid to musicians or music clerks in the church minutes. It is no great surprise that a person such as William Walker would spring from this background. In 1826 his parents removed to Spartanburg District, and joined Cedar Springs Baptist Church. Here Walker met his future wife, Amy Golightly. William Walker and wife were dismissed from Cedar Springs on May 23, 1835, and probably at that time removed to the town of Spartanburg. His cousin, the Rev. John G. Landrum, became the first pastor of the Baptist Church in that town in 1839. That relation may have influenced Walker’s location there and the association with that Church.

In 1835, William Walker published the first edition of Southern Harmony. It was well received and went through several subsequent editions. The Sacred Harp preserves a tradition that Benjamin Franklin White (who married Thurza, sister of Amy Golightly) was actually a co-author of Southern Harmony but was given no credit [a debatable claim not repeated in the 1991 edition - ed.]. Some time after this, B. F. White and family moved to Harris County, Georgia, where he co-authored the Sacred Harp with E. J. King. It seems likely that White had made a contribution to Walker’s book, since the two are similar in content and format. William Walker (who became known as “Singing Billy”) used the initials A. S. H. (Author of Southern Harmony) and said that he would rather have this ascribed to his name than P-R-E-S.

©1979, Brent Howard Holcomb, used with permission